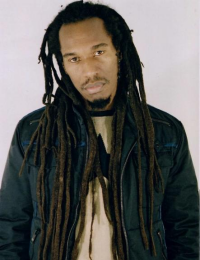

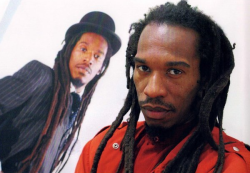

Benjamin Zephaniah Interview

Radical poet, musician and passionate vegan Benjamin Zephaniah talks respect, feline friendships and raising the next generation.

Radical poet, musician and passionate vegan Benjamin Zephaniah talks respect, feline friendships and raising the next generation.

Benjamin Zephaniah is not one for labels.

'I'm black and I'm Rastafarian and I'm a vegan and I'm lots of other things. I don't want to be known as a black poet or as a Rastafarian poet or a vegan poet. I just happen to be black. I just happen to be vegan. I'm just me.'

His innate refusal to be categorised, combined with his irreverent lyrical gift, has brought Benjamin international critical and political reverence.

From his first public performance as a 10-year-old in a Midlands church to his rarefied status as one of Britain's most respected postwar writers – via his very public rejection of an OBE in 2003 – he's never been afraid to follow an alternative path and has turned his instinctive ideological dissidence into a compelling asset.

The only labels the well-travelled 52-year-old does recognise are the ones on the strictly vegan food that he consumes.

'I always read the labels,' he says, 'whether I'm in a health food shop or a supermarket – and I don't go in them very often – because I want to know what's in the food I'm putting into my body. I care about the quality of the food and I care about me.'

And in answer to critics who label vegans as eccentrics, he says, 'There's nothing extreme in caring about yourself and caring about animals.'

Benjamin Zephaniah's veganism is very much a product of his upbringing.

Born in April 1958 in Birmingham's Handsworth, 'the Jamaican capital of Europe', as the only black child in his primary school, his ethnicity informed his early opinions.

'I suffered racism at school – and the loneliest place in the world is the playground, when nobody wants to talk to you and everybody else is really happy playing.'

Consequently, young Benjamin began to search out company elsewhere.

'I started to make friends with the local cats. They're ritualistic animals and I'd meet them in the same places at the same times at break or lunchtime, and even at that very early age I realised they were judging me only because I was friendly or whatever. They weren't being racist and they weren't forming organisations to get rid of me.

'Animals were my friends. I may have seemed a bit crazy at the time but I would actually talk to animals. And it's still a habit I've got now.'

'Animals were my friends. I may have seemed a bit crazy at the time but I would actually talk to animals. And it's still a habit I've got now.'

Aged six or seven, Benjamin reluctantly ate meat, baulking at the texture, but it wasn't until a conversation with his mother that his eventual views on meat-eating were first cultivated.

'I was 13 and I asked her where meat came from and she told me it came from an animal. I remember being horrified because up until then I just didn't associate meat with animals. I just knew I didn't like it very much.

'I replied, "I don't eat my friends" and then kind of smiled. I didn't say, "I'm going to be a vegetarian" as I didn't even know what a vegetarian was. I just said, "I'm going to stop eating meat." My mum smiled and said, "Okay, it'll be a couple of weeks and you'll be back." But I haven't touched meat since.'

So what's a vegan?

Within months, Benjamin decided that digestive denunciation of animal products didn't sufficiently address his concerns, and vowed to eradicate the consumption of anything animal-related, including leather, dairy products and eventually even honey, from his lifestyle, but his linguistic sophistication had yet to match his ideological maturity.

'I remember this kid coming up to me and I refused a lick of his ice cream. He said, "You're a vegan" and I went to hit him. I thought it was a really horrible word. I'd never heard it before. I said, "Who the f*** are you calling a vegan?" and he said, "No, vegans are good people; they're compassionate."'

Thirty-nine years later and Benjamin, who runs and meditates every day, is adamant that his veganism has been pivotal to his continuing good health.

'I was a very sickly child and would be in and out of hospital regularly for various ailments, but today when you put me in a photo with my younger brother and sister everyone thinks I'm the youngest.

'I saw my doctor yesterday and he said that my blood pressure and some of my blood readings are those of a 25-year-old, but I've always taken my veganism seriously.

'There is such a thing as being a bad vegan, especially if you're doing exercise and not getting enough protein or carbs. Some people think that a vegan meal is meat-and-two-veg minus the meat, but you've got to replace the protein and try to replace the missing nutrients and vitamins you would've got from a meat-eating diet.'

As well as the physical benefits of his lifestyle, Benjamin is grateful for the meat-free psychological harmony.

'When I eat I have a clear conscience. If you are a part of this murder machine, regardless of what people say to defend themselves when they eat meat, it's lodged in the back of the mind that you are dealing in death.'

It's exactly this type of evocative language that has earned Benjamin a place in The Times newspaper's top 50 postwar writers and won him speaking invitations from some of the world's most influential opinion-formers, among them Nelson Mandela, Maya Angelou, Michael Mansfield QC, Salman Rushdie and Tony Benn.

His work, variously described as 'street politics', 'dub poetry' and 'sociological critique', bridges the gap between verse, song and performance art and has been prolific. His mushrooming back catalogue includes 15 poetry collections, five novels, several plays and albums, and a clutch of children's books.

The subject matter varies but the creative catalyst is consistent.

'I don't like to see myself as a political activist. I'm just reacting to the stuff that affects me.

Like the conditions I lived in as a kid, the BNP and the National Front attacking us on the street, right through to the present day to the country going to war. It's my duty to react to it.

'I just write about things I'm very passionate about. My next novel will concentrate on the concept of democracy. Sometimes I'll write about race and other times I'll feel like writing about animals.'

A well-rounded approach

Benjamin's most famous vegan work is his children's anthology of poems, Talking Turkeys – 'Except when I wrote it I didn't think it was a vegan book,' he argues.

'I didn't actually sit down and plan to write a vegan poetry book. It just happens to

have a lot of stuff about animal suffering in there, although that book got such a positive reaction I did sit down and write The Little Book of Vegan Poems afterwards.

have a lot of stuff about animal suffering in there, although that book got such a positive reaction I did sit down and write The Little Book of Vegan Poems afterwards.

'Despite that – and this may sound contradictory – I don't want to be knocking it down people's throats. I want to get on with my life. And when I meet someone and every second word is "vegan" I think, "Come on, man, there's meat-eaters who may be put off by that." It's much better that they see that you're a rounded person and you get on with your life and you're not going on about it all the time.'

Despite his reticence to publicly bang the vegan drum, divorcee Benjamin, who lives alone in a Lincolnshire village after stints in London, Indonesia and China, is unequivocal in his personal views.

'I'm single right now and I've never had kids, so it's difficult to know how I'd deal with the vegan issue with the next generation, as you never know until you're there.

'Some people say that they'd let their kids eat meat until they were old enough to make up their own minds, but I'd say the opposite. If I have children they'll be vegetarian in my house and make their own choices when they're older.'

The same goes for his friends.

'I won't even allow people to bring meat into my house. If somebody has brought meat with them, I won't allow it in. They can sit in the garden and eat it. And they can take away the rubbish, too – I don't want the bones in my garden!

'This is my ideal, my environment and when friends visit I'll just say, "no meat" in the same breath that I'll say "no smoking". It's all about respecting people's beliefs.'

Interview source:

www.vegetarianliving.co.uk/interviews.php?do=view&article=10